Lessons learned building safia, from idea to a working protype

During my business prospection travel in Congo in 2024 after more than 20 years living in Belgium. I closely observed the deterioration of security compared to my memories. During this travel, I had the opportunity to discuss with locals and family members, I understood how unsecure people can feel.

This travel has since changed my view on the world and how to do business. I kept thinking about how I could contribute to helping people.

For months, I was thinking about what I could do, then after a discussion with an academic living in Congo in late 2024, I started to elaborate on how to provide people with helpful security insight. Then in February 2025, the expected conflict with the M23 rebel Group escalated, first in Goma in North Kivu followed by Bukavu in South Kivu.

We then decided at Ntbies, in collaboration with Giacomo Giannelli from GiiStudio, it was time to take action and develop something that could help people to avoid confusion that happens during crises and the lack of reliable information.

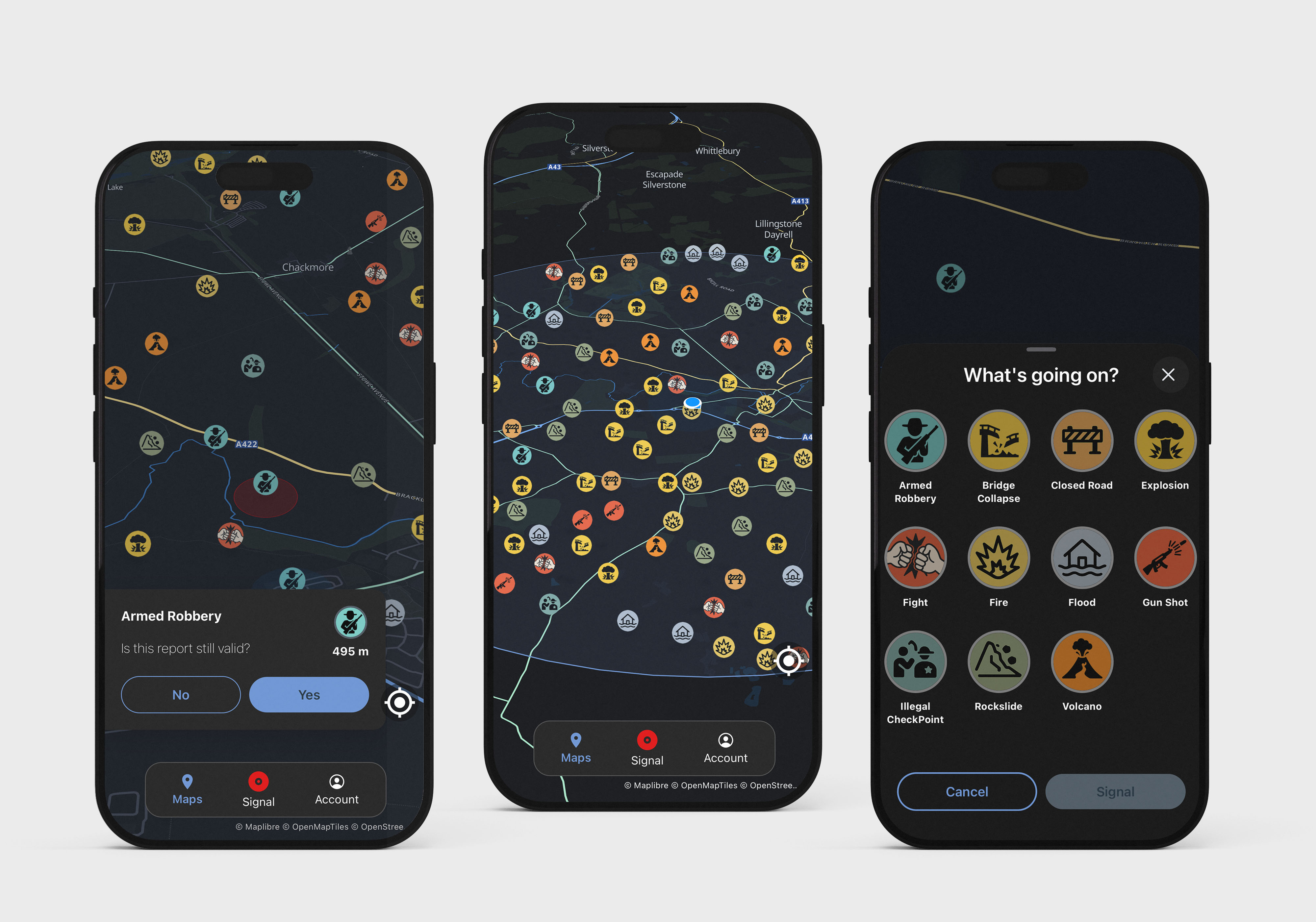

When we first imagined Safia, we had many ideas. But we were sure we needed to build something simple, something that could allow people to report what was happening around them and display those reports on a map to allow neighbours to make safer decisions. The concept was simple, but the path to a usable prototype was not that simple. The project forced us to rethink everything from how to handle privacy and deal with geographic data to how we would define "real time."

Here I'll walk you through not just the technical decisions we made, but even more, how the lessons learned from this project have shaped the way at Ntbies we will handle challenging projects in the future.

Purpose not Engagement

Since the beginning of the project, we've made the decision about what we wanted Safia not to be. It was clear to us that the world didn't need another social network. In the crisis, likes, comments, or debates can create useless noise. People need facts.

To strip the noise, we decided to design reports as structured signals designed to protect. This decision liberated us and helped us make the right choice during the design of the interface but also when choosing the backend architecture.

We got rid of the temptation of building something addictive instead of building something useful.

Removing the Friction

When we started to build the prototype, we realized something important. A safety tool is useless if it's hard to use and hard to understand. When people are witnessing an incident or fleeing a danger zone, they do not have time to navigate many layers of a menu.

To tackle that issue, we designed an interface so that a user can open the app, and submit an incident report in second.

The obsession with making the usage of Safia simple became the backbone of the product.

Privacy by design

Dealing with people's safety in a danger zone makes privacy an important issue. We could not take the risk of having to react to them, but we decided to make them less likely to arise.

We made a structural choice of decoupling user identity from incident reports. While Firebase handles the login while our Go backend stores incidents in our database with no link to the users who have submitted them. We also decided to only keep the last known location and not the user's known location history.

It is impossible to build trust without making sure anonymity enforcement is structural.

The Reality of the Map

During the implementation, we realized we could not rely on generic external map tile providers, such as Google Maps, Apple Maps, or Mapbox. So we made the decision to host our own maps tiles on Cloudflare R2. It was more work (we will dig into the subject in the future) and more challenging than expected, but it was important as we had control over the design and the map to use.

In regions like the Democratic Republic of Congo, connectivity can be an issue for some users, having an optimized, fast loading map is essential and not a luxury. We also had to accept the fact that technology can't do magic even if sometimes users expect it to. GPS is not always exact, provided coordinates can depend on the strength of the signal, the quality of a device, the surrounding buildings, and stateliness coverage of the region. We decided to consider coordinate transmitted with the report as absolute truth but approximate one. Grouping reports based on proximity helped us create a map that takes into account the messiness of real-world data.

Instead of making the real world adapt to the technology, we made the last one adapt.

Speaking the Language (Literally)

Safety being cultural, building a tool for the local community can't only support English or French. It was important to us to have as many local languages as possible.

The prototype was lunch with support for Swahili, Lingala, English, French, German, Dutch, Portuguese, Spanish, and Italian. This was not just a translation feature, but a requirement for the app to be usable by as many people as possible. Especially if we consider the fact that danger is described differently across languages.

It's important for a tool intended for the broader public to feel like a local tool, not something imported

Know when to say "No"

One challenging decision we made was to exclude features that we had already built or that were easy to build. One example is allowing people to attach images or video to the report. This carries a massive risk, it could allow identification of victims or expose the location of people hiding. Having a moderation team and robust ethical safeguards is a must.

Sometimes, it's important to choose caution over complexity. For this project at Ntbies, we chose the first one.

Perhaps the hardest decision was excluding features we had already built. Our tech stack supports image uploads, but we disabled them. Why? Because photos carry massive risks. They can identify victims or expose the location of people in hiding. Until we have a robust moderation team and ethical safeguards in place, we chose caution over complexity.

A Prototype Built on Experience

It took us 5 months to build this prototype with its secure authentication (thanks to Firebase), and real-time updates. This prototype is a collection of lessons learned the hard way. We will dig deeper into them in future articles.

Building Safia in this short period has changed, not only how I, but how we approach technology. This project has taught us that cultural understanding is a feature of the engineering discipline.

We are still working on the integration of many features, but we are glad the foundation of this solution is rooted in the reality of the people we built it to serve.